The First States

In his book "Our Kind" Marvin Harris states:

In the earliest centers of agriculture and stockraising, people depended on rainfall to water their crops. As the population increased, they experimented with irrigation and began to fission off and colonize the drier parts of the region. Sumer, situated in the rainless but swampy and flood-prone deltaic zones of the Tigris-Euphrates, was settled in this manner. Confined at first to the margins of a natural watercourse, the Sumerians soon became totally dependent on irrigation to water their fields of wheat and barley, unknowingly trapping themselves into the final condition for the transition to statedom. As their would-be kings pressed for more taxes and more public labor, Sumer's commoners found that they lost the option to move out. How could they take the artificial waterways and their irrigated fields, gardens, and orchards, representing the investment of generations of labor, with them? To live away from the rivers, they would have to adopt a pastoral nomadic way of life for which they lacked the prerequisite skills and technology-

Archaeologists are not able to say exactly where and when in Sumer the transition took place. But by 4350 b.c., mud-brick structures with ramps and terraces called ziggurats, combining the function of fortress and temple, began to loom over the larger settlements. Like the mounds, tombs, megaliths, and pyramids found throughout the world, ziggurats attest to the presence of advanced chiefdoms capable of organizing large amounts of donated labor and were the forerunner of the great tower of Babylon, which was over 300 feet high, and of the Biblical tower at Babel. By 3500 b.c., there were streets, houses, temples, palaces, and fortifications covering several hundred acres at Uruk in Iraq. Perhaps the transition occurred there. If not, it took place at Lagash, Eridu, Ur, or Nippur, all flourishing as independent kingdoms by 3200 b.c.

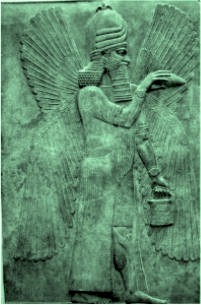

Driven by the same internal pressures that sent chiefdoms to war, the Sumerian kingdom had one important advantage. Chiefdoms were likely to try to exterminate their enemies and to kill and eat their prisoners of war. Only states possessed the managerial know-how and the military might for extracting labor and resources from conquered people. By aggregating defeated populations into a peasant class, states rode an amplifying wave of territorial expansion. The more populous and productive they became, the greater their power to defeat and exploit additional peoples and territories. At various times after 3000 b.c., one or the other of the Sumerian kingdoms held sway over Sumeria. But other states soon formed farther upstream on the Euphrates. Under Sargon I, in 2350 b.c., one of them conquered all of Mesopotamia including Sumeria and lands extending from the Euphrates to the Mediterranean Sea. For the next 4,300 years it was one empire after another: Babylonian, Assyrian, Hyskos, Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Arabian, Ottoman, British. Our kind had created and mounted a wild beast that ate continents. Will we ever be able to tame this, our own creation, the way we tamed nature's sheep and goats?

|