|

|

|

|

|

Does Power Destroy Us?

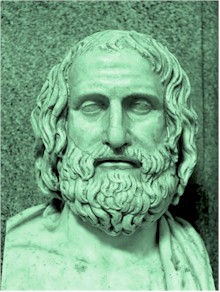

Those whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad.

Euripides (c. 480BC-406BC)

Other have said "Those whom God wishes to destroy, He first makes mad with power."

Why would power drive men mad? Is power something foreign to our nature? Is it like the genie in the bottle, that once released we cannot fully control?

To find answers to such questions, we must look to antiquity and learn where this first became an aspect of human experience.

|

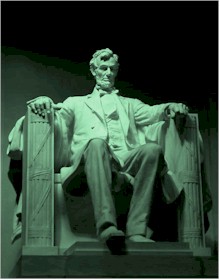

To test a man's character, give him power.

"Nearly all men can stand the test of adversity, but if you really want to test a man's character, give him power."

-- Abraham Lincoln

Why would power be the ultimate test of a man’s character? It would seem counterintuitive. Would not adversity, hardship, misfortune, danger, and harsh conditions, test a man more than his having power. It would seem that power would make things easier to manage and bring out the best in a man.

Unless, of course, power is unnatural and our brain is not wired in a way that it can fully cope with having it. Is that possible, and if so, just why would that be?

|

Squirrels, What Don't They Know?

Did you ever observe that squirrels have great difficulty when they encounter a vehicle on the road?

They seem to be perplexed by the very concept of some non-animal, physical object that can come at them as they attempt to cross a roadway and possibly cause them great harm.

Is it because fossils record the evolutionary history of tree squirrels date back to the Late Eocene Epoch (41.3 million to 33.7 million years ago) in North America and their brains were designed by adaptations to past environments?

Perhaps such squirrel brains are still adapted to their environment of evolutionary adaptation and are ill equipped to deal with surroundings that include the technology of automobiles. Likewise our unconscious minds, adapted to the ancestral existence of hunter-gatherers and the social structure of that environment, would be ill suited to cope with civilization and its attendant power structure based upon institutions that can bestow un-consented power to a boss.

|

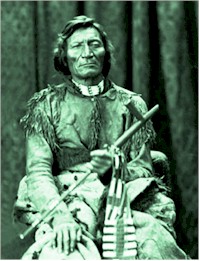

The Good Chief

G.B. Grinnell in his book “The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Ways of Life” describes the leadership of these North American hunter-gatherers as follows:

A good chief gave his whole heart and his whole mind to the work of helping his people, and strove for their welfare with an earnestness and a devotion rarely equaled by the rulers of other men. Such thought for his fellows was not without its influence on the man himself; after a time the spirit of goodwill which animated him became reflected in his countenance, so that as he grew old such a chief often came to have a most benevolent and kindly expression. Yet, though simple, honest, generous, tenderhearted, and often merry and jolly, when occasion demanded he could be stern, severe, and inflexible of purpose .... They were like the conventional notion of Indians in nothing save in the color of their skin. True friends, delightful companions, wise counselors, they were men whose attitude toward their fellows we might all emulate.

This was the type of leadership our ancestors experienced during the tens of thousands of years that the brain and emotions of modern Homo-sapiens were evolving and this leadership by consent bears no relation to the tyranny of power in this modern world. As we have seen, it is only through the biologically unfamiliar circumstances of civilization that the kind of top-down hierarchy, the un-consented boss, the bureaucratic official, the dictator can emerge. It is as foreign and unfamiliar to our nature as any motor vehicle is to a squirrel, and we are equally unprepared to deal with it as either the ruler or the ruled.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright by OnHumanNature.com 2008

|

|

|

|